Isabelle LASSIGNARDIE

The Forest: An Object of Fascination

2004

The forest and the tree have always been a fascinating subject, symbol and fear, often linked to a sacred and divine dimension through their metamorphosis, their unremitting growth and the power they represent.

In these introductory paragraphs, we will try to define some of Christophe Doucet's works, following the vital lead of both the tree and the forest.

The role played by nature, and more particularly by the forest and the tree, in Man's collective imaginary, is brilliantly noted and studied by Robert Dumas in his Traité de l'arbre, Essai d'une philosophie occidentale (Actes Sud, 2001), and by Robert Harrison in Forêts, essai sur l'imaginaire (Flammarion, 1992).

The Workshop

Christophe Doucet's workshop is an amazing place, an image of his personality. Located near the forest, in the Landes, it is an old resin distillery, an area of 500m². Natural environment is an integral part of Christophe Doucet's working place, of creation. It is a vast space, widely open to the outside, flooded with light. First and foremost, it is a place of creation, of work, and you can feel it as soon as you get there.

Old works are stored here, others are in process. Trunks rear up from everywhere between tools and machines, a metal kiln, saws, compressors. The whole evokes a kind of weird bazaar and we can't say if some of the trunks are completed or still in progress; dust invades the space and his works, far away from a sterilized space!

Yet each object seems to be in its proper place but with a specific coherence by the artist. Some of the works are outside, some tools too, a joyful scattering. All of a sudden we wonder whether the workshop is really inside or if it is spreading out towards the surrounding forest.

A shed is used as a storage spot. I had the impression that Christophe was (re)discovering some of his works at the same time as I did; he even sometimes seemed to be amazed at their existence, their presence! This reaction reveals a certain simplicity of the artist; his works are like moments that he seems to be suddenly rediscovering!

His workshop is not a showplace; he does not use it to exhibit his creations. They are dusty, at the mercy of bad weather, of time passing.

A Permanent Dichotomy

Forest marking, between archaism and erudite calculations.

The first artistic meeting between Christophe Doucet and the forest universe gave place to photographic snapshots of the blazes left on the trees by the foresters. These marks are traces of painting, plastic stripes girding the trunks (...) Their initial function is to delimit the forest, i.e., to carry out a precise geometrization of the natural forest space, a delimitation which immediately evokes that of a sacred space.

This type of marking also reveals a duality, an inherent dichotomy. Indeed, these marks refer to signs, to codes; they answer a logic, a methodical reading of natural spaces. An ambiguity is perceptible within the marking process: these signs result from simple and rough methods, and even mechanical ones; they are simple and rough traces of painting, suggesting spontaneity. Their role is to be functional, convenient, and legible. However, despite their rough and very simple aspect, their arrangement in the space is the product of calculations, of a specific organization of plots of land. Thus, a duality appears between the plastic nature of these signs and their natural use, which answers a coherent and precise work.

Through his meeting with the Land-artists, Christophe Doucet realized that the foresters did act on nature, but without any artistic consciousness. So, via photography, he turned these automatic signs into works of art. An ambiguity is then perceptible in his work, the same as we have noticed through forest marking.

A Formal Duality, Between Brutality and Sophistication

Dichotomy is noticed in most of Christophe's works, particularly in the way he treats material. Indeed, many works present a raw aspect; we notice some wooden pieces, scarred with traces of wide and rough slivers: the surface is not smooth, it scratches, metals are attacked by rust. And yet, the metal parts are very finely worked with sophisticated arabesque-like forms.

Through his work, Christophe Doucet insists on the action of Man and his appropriation of material: the capacity of Man to transform material, offering it an outline which is not always natural while preserving its essence.

From this point of view, the opposition appears through the example of the paper bathtubs covered with gold sheets: a cohabitation of the rough aspect of paper with the smoothness and preciousness of gold. Isn't it an image of the famous Nietzschean couple: the mask of the Apollonian appearance confronted with a Dionysian brutality?

Nature: Creation and Violence

This confrontation, which his work inherited, seems to synchronize with the very idea of Nature.

Nature embodies the idea of a creative force, comparable to a divine force, giving way to "Mother Nature," symbol of fertility. However, according to the creative myths, violence seems rigorously associated with the act of creation. In reference to Jean-Pierre Vernant's writings about the creation of the world in Greek mythology, and more particularly, to the "rip" between Ouranos and Gaïa, it is obvious that the extreme violent act here gives birth to the very principle of creation. In the same way, René Girard speaks about a "founding violence" in La Violence et le Sacré. In his book, he demonstrates the omnipresence of a violence which always precedes the act of creation. Moreover, according to Girard, sacrifice is a necessary act for the expression of violence that the human and mortal being keeps repressing. The author also evokes the concept of a "scapegoat victim," the lucky one selected randomly which will undergo a sacrifice, as in Spartes in Antiquity. Or the Greek gods who embodied the creative forces and had power of life and death. So it seems that Nature, as a creative power and because of the disasters it may generate, can operate a random selection of its "scapegoat victims."

In his work, Christophe Doucet seems to approach the idea of Nature through its violent and powerful aspect.

A Violent Nature

Against a Romantic Idea of Nature.

If Nature is Christophe's main material, it doesn't mean that his apprehension of Nature corresponds to the traditional vision, conveyed among other things by the Romantic movement. He is not in search of a physical and spiritual osmosis with Nature, and he makes a point of specifying it: "I do not form a unit with it." In his mind, Nature is no longer a protective power as it used to be for some fugitives or outcasts who took refuge in the heart of wood and forests. The forest has a sacred meaning of divine protection, incarnating the power of the natural forces on its own. In the same way, the sacralization of natural spaces results from the fascination of Man for this fertile supreme force which keeps metamorphosing according to regular cycles. Lastly, Nature does play an undeniable nourishing role, as much towards fauna and flora as towards human beings who still draw food and wood from it. The role of Nature is comprehensive: refuge, protection, nourishing mother.

Such a thought could be the Deep Ecology Movement's motto; for them, Nature is a benevolent being which is to be protected and preserved without limit. From an artistic point of view, this process might be illustrated by Nils-Udo's works (we'll refer to him later) which perfectly evoke the ultimate aspiration, forming a total unit with natural elements. Yet, Christophe, because of his artistic reflection and actions, opposes Nils-Udo's works; he tackles the forest domains under a watchful eye of his profession: "the forests of France, and particularly in the Landes, are cultivated, i.e., that trees are planted or sown in order to be exploited fifty or eighty years later. Contrary to a generally accepted idea, a badly-kept forest without any wood cuttings is a dying forest. Forestry contributes to the forest's vitality. In a way, with my sculpture, I contribute to the forest's life."

Christophe Doucet thus opposes the Deep Ecology preachers' actions against any kind of forestry. The idea of nature, quoted previously, can be illustrated by a series of Nils-Udo's works: "Lavender Nest," in 1988, built at Crestet in the south of France; or "The Nest," in 1978, showing the naked artist as "an anthropomorphic animal born from the improbable clutch of a giant bird," according to Tiberghien in Nature, Art, Paysage.

The man stays out naked and vulnerable, in a fetal position, as an infant in the shelter of his mother's womb which is embodied by the nest. The message is, here, legible, the nest being a form close to the womb's, an evocation of the cycles which rule the human being (day, night, biological cycles); Bachelard, in La Poétique de l'espace, thus speaks about "the round being," "being is round."

Vegetable nest, female "nest"...

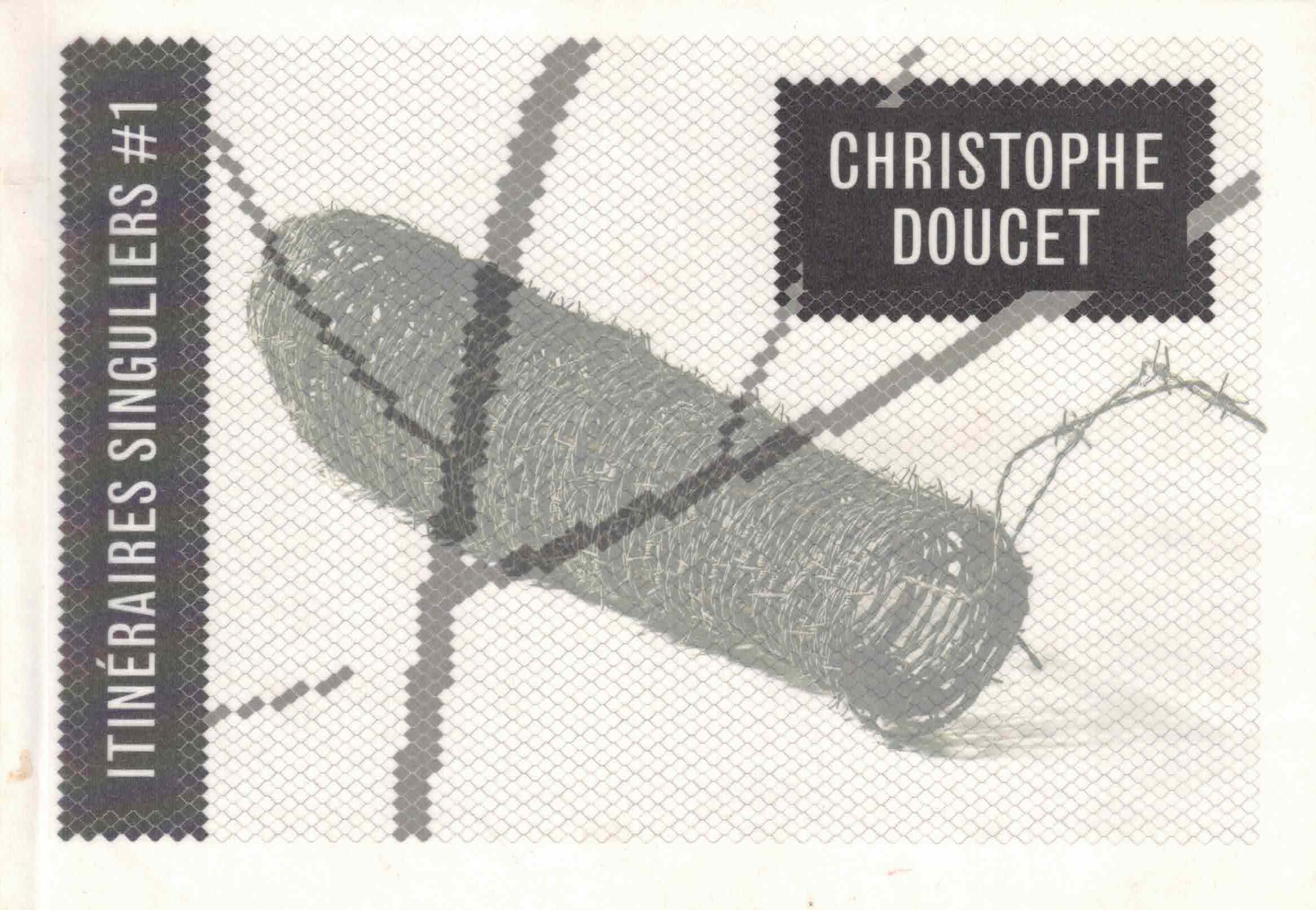

The image of the nest appears in Doucet's work and a comparative study of each vision suggested by both Udo and Doucet can prove to be interesting. Indeed, if Udo's human-sized nest seems comforting, Christophe Doucet's ones hardly convey the same feeling. His nests are composed of plants, but they are thorny and barbed wired. Here, he offers a different interpretation of the nest; it is threatening and rugged, it represents a danger. The danger is all the more subtile since at first sight, if the spectator stands aloof, the nest seems ordinary, yet he will have to get closer to feel the risk, this very threat which watches anyone who is in search for some comfort. Nature becomes synonymous with suffering and violence.

Such a violent nature is also meaningful in the anthropomorphic sculpture. If we refer to "hoop-net works", their aspect does evoke female genitals. The analogy Woman/Nature is immediate, both are creative forces and mothers. These hoop-nets are made of rusted wire- netting, barbed wire and strings of wire, they seem to be traps. This parallel, between a violent nature and the female body, is upheld by the fact that nature is the protagonist of the process of a ceaseless creation according to precise and regular cycles, and of the principle of "Mother of the World" together with her animal, vegetal and mineral elements. Moreover, some recent works of the artist indirectly evoke the series of the "Multiplications des Centres" by Louise Bourgeois.

The tree and the death...

This anthropomorphism between tree and nature is displayed in the series "Boîtes" : human-sized wooden works. These boxes present several aspects. First of all, they question the concept of space, also a valid question concerning the hoop-nets : the full, the empty, the inside, the outside. But Doucet's boxes and hoop-nets are not enclosed nor can they be, and thus they have a seethrough dimension, nothing is dissimulated.

Moreover, these works, according to the artist's will, are a clear evocation of what will be "his box", i.e. his sarcophagus, his death. Bachelard, in "Droit de rêver", refers to an engraving by Albert Flocon and raises an essential question : "Is the tree an erected sarcophagus which is to devour some human flesh [... ]? ". These boxes illustrate the destroying and dangerous aspect of nature, a nature violently out of control, itself at the origin of our existence, but which might be a a reason for our disappearance. Only one certainty, the earth will be a shelter, for us and our sarcophagus...

This combination brings strange relations between nature and death, the tree and the sarcophagus, and it is clear that Christophe Doucet, through his work, places nature well beyond the traditional iconography of a benevolent and maternal nature!

Need for protection

The shed, a sure refuge...

In "Nature, Art, Paysage", Gilles Tiberghien deals with shelter as a primitive shed. He mentions Vitruve's "Ten books of architecture", refering to fire, the first social sediment which prompted mankind to communicate, and gave them the opportunity "to gather and live together". " So they started making sheds out of leaves [... ], places where they could shelter", Vitruve writes.

Primitive architecture, such as it is imagined, also refers to natural formations, cavities in the mountains, to find protection as in a burrow or a bird's nest for example. We have already noticed in Christophe Doucet's work that the nest is no longer a shelter nor a refuge. However, he has realised a series of works around the idea of the shed, but they are not made on the animal model, they are neither nests nor burrows, but genuine architectures made by human beings. They result from an association of materials provided by Nature and the spirit of Man.

Here Doucet refers directly to the foresters' sheds. He often quotes Brancusi who drew his inspiration for his "endless columns" from the columns of the Rumanian settlements. Christophe re-creates the shelters, omnipresent in the Landes forest. These sheds, in the depth of natural spaces, are used to store the material but also a refuge. The artist asserts the vocation of his sheds as a means for selfprotection against hostile nature.

It seems these sheds pay homage to the work of Man on Nature; moreover, together with photography on marking, Doucet shifts functional pieces of work into the field of art, and so doing he provides an artistic awareness to the forest sheds.. This diversion seems to be a tribute to human art.

The "tool-works "

This process is being expressed through the series of "tool-works ". The tool, in itself, symbolizes technique; Man takes materials from natural surroundings in order to materialise a concept and give it a frame and a function. Thus, Heidegger distinguishes the thing, the tool and the work of art : the thing, which is conditioned by its natural environment; the tool differs from the thing by its use, its form resulting from a human action; the work of art, as a creation of the spirit, shares a common point with the tool.

So would Christophe Doucet's tools become works of art by the fact that they are unusable?

On this subject, Anna d' Andriesens relates "tool-works " to tools discovered during archaeological excavations : "Some archaeological objects, often among the most attractive ones, confront the specialist with a problem of identification. They seem usable but some of their elements are so atrophied that they no longer fulfill what seemed to be their purpose. "Doucet's tools are oversized, others seem very realistic... "

Is it a commemoration? Do they pay homage to the earliest tools (yet still current, as most of them are much the same as their initial form), to the first expressions of technique ? This idea of technical beginnings is confirmed by the title given to these installations,

"Lab-installations... an experimental flavour" ! Tools symbolize the first steps towards Man's domestication of natural spaces; they represent one way the animal became Man.

Votive objects.

Christophe sets his "tool-works " meticulously inside each shed, referring to votive tools left against an altar. About these installations, Anna d' Andriesens has noticed "this very place precisely assigned to each of these singular tools, which makes part of their utilitarian and ritual functionning ".

Do these sheds evoke a temple or a makeshift altar ?

As a matter of fact, a benevolent and comforting atmosphere emanates from these shed/tool-installations : they offer the public both a material refuge and a metaphysical protection against a fascinating nature, by its unpredictability and its violence, but also by the link it has always maintained with human nature.

Traduction Maïté PRADEL